- Intro, scope and aims

- About Willow

- So, what is CHC funding, and how do you get it?

- A critical investigation and reflection of the CHC assessment process

- Recommendations & avenues for change and transformation

- Conclusion

- References

- Call for comments

Intro, scope and aims

Navigating the complexities of Continuing Healthcare (CHC) funding can be a daunting and challenging experience. This blog post will share our firsthand journey through the CHC funding process and provide critical reflections and suggestions for improvement as a critical psychologist. Here, the challenges of the process will be examined while suggesting possible alternatives and avenues for social change, in addition to individual recommendations for those who are now amidst the CHC process, to shed light on the nuances of CHC funding and advocate for a more transparent and equitable system for all.

About Willow

Willow has a long list of complex medical conditions (which I am not privy to share here to maintain her anonymity), which worsened after a series of TIA’s and a major stroke, which left her unable to move and unable to make decisions for herself. At this point, she was moved into a nursing home as she could no longer care for herself and her numerous complex conditions. As such, she more than meets the criteria for CHC (continuing healthcare) funding. Willow had two reviews covering two periods while receiving FNC (funded nursing care). The first of which went all the way to the ICB panel (who independently review assessments after the internal appeals process). The second covered a period after Willow’s condition worsened, and we won.

This is our and Willows’ story of obtaining CHC funding, alongside critical commentary and suggestions to improve the CHC assessment process.

So, what is CHC funding, and how do you get it?

According to the NHS, CHC funding is solely NHS-funded care, which can be provided in numerous settings, such as a nursing home, whereby the NHS has deemed said person to have a ‘primary health need’. Clinical commissioning groups in England make NHS CHC funding decisions; our experience was with the Midlands Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust.

Eligibility relies on the interpretation of whether the person has a ‘primary health need’, yet there is no legal definition for this, and the Government has attempted to standardise the interpretations of this statement across local bodies that conduct assessments through a framework (issued in 2022). The framework also aims to give assessors further guidance around what should/should not be used to judge eligibility. For further insight, see the NHS CHC government guidance.

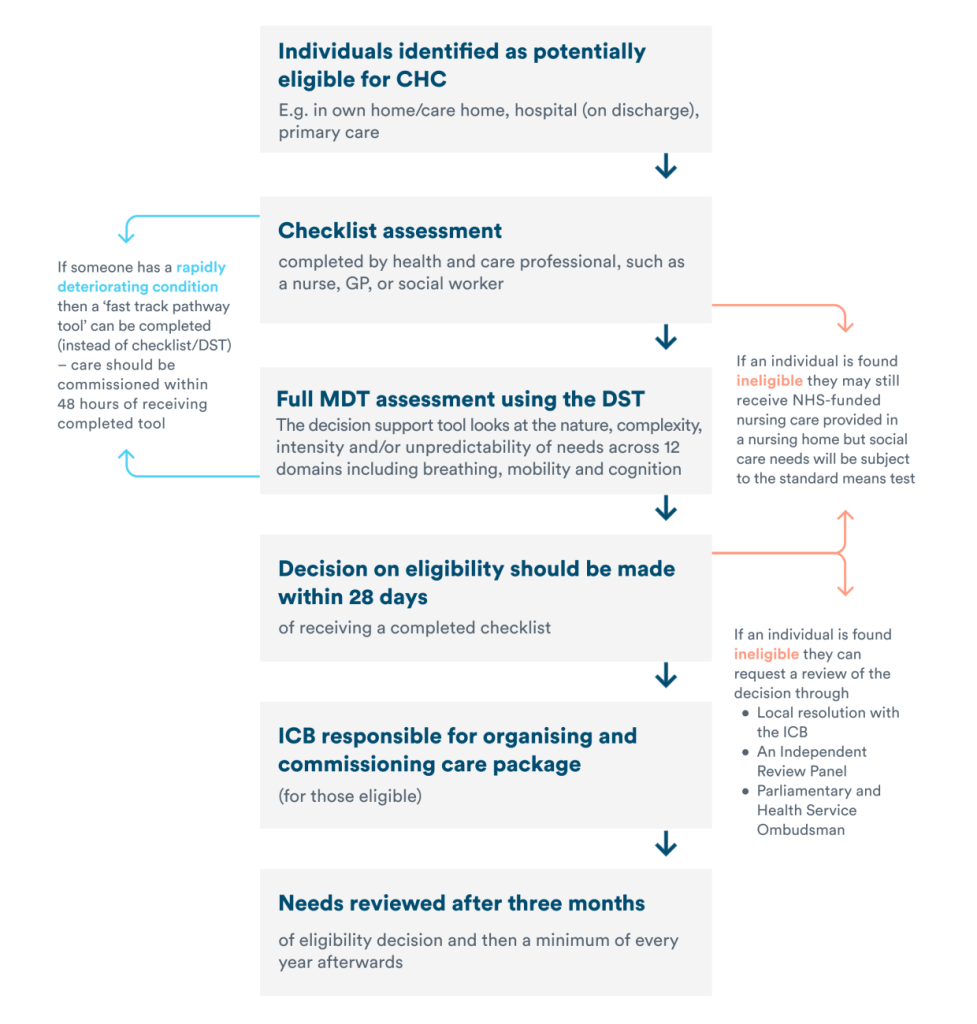

An initial screening is first completed, usually by a healthcare professional, to determine those who may broadly meet the CHC funding criteria and can be referred for a full assessment using the NHS continuing care checklist. If someone needs urgent care, they are assessed using a different tool: the Fast Track Pathway Tool, designed for those with a rapidly deteriorating condition and entering a terminal phase. If deemed eligible for a full assessment, this will be conducted by a “multi-disciplinary” team (MDT) from your local clinical commissioning group, comprised of at least two health or care professionals who are already involved in the patient’s care; for us, this was Willow’s regular nurse and home care manager, in addition to NHS assessors. The assessment uses the CHC Decision Support Tool (DST). The MDT will allocate a score for each of the 12 care domains: either no needs (N), low (L), moderate (M), high (H), severe (S) or priority (P) levels of need. Assessors will also apply the primary health need indicators where applicable: nature, intensity, complexity, and unpredictability; see the diagram below. For more information, the Law Society provides an excellent overview of CHC eligibility.

See the below flowchart for a better understanding of the process.

As will be discussed, the assessment process is fraught with challenges, making it difficult for many to be deemed eligible for CHC funding. In Q4 2022-23, 45,375 people were referred, but only 29,634 were assessed as eligible, a lower number than in previous years (e.g., 54,498 in 2021/22). Most of these were eligible via the Fast Track assessment route for those with a rapidly deteriorating condition and entering a terminal phase. It is much more challenging to obtain funding through the standard pathway; the Standard NHS CHC referral conversion rate was 16%, and the Fast Track referral conversion rate was 96% (NHS).

If, after the assessment, you are not happy with the decision made, as we weren’t, there are multiple pathways to appeal the decision:

- A local review and resolution process run by the Integrated Care Board (ICB)

- A request to NHS England for review by an Independent Review Panel

- Referral to the Health Service Ombudsman (to ensure correct proceedings, not question decisions).

We pursued the first two of the above three avenues and have yet to move to the third option. Usually, the Ombudsman would require that other options have been pursued beforehand, that there has been a complaint made directly to the NHS organisation, e.g., the CCG/ICB and that you provide the following: details about your complaint; when it happened; how it affected you; what you would like done to put things right; if you are planning or have taken legal action; if you are complaining for someone else.

Therefore, keeping accurate documentation of your experience throughout, including maintaining or creating a paper trail (to put your challenges, complaints and requests in writing and request written responses), is vital to ensure that you can complain to the Ombudsman; with this, it may be easier to substantiate your complaint. I would advocate for keeping a journal throughout the process, gaining a representative if you can, and ensuring everything is documented in writing. This may also empower you and give you control over the situation.

A critical investigation and reflection of the CHC assessment process

A Critical Commentary

As a critical health and social psychologist, the following commentary is underpinned by values around exposing and resisting oppression. Critical psychology is broadly concerned with justice and often moves beyond individualistic conceptualisations of issues to focus on the social reality and institutions or groups occupying positions of power (Teo, 2021). For example, as critical psychologists, we can only talk about problems with CHC funding by analysing how our neoliberalism and capitalist society impact such experiences and individuals. We aim to make the political explicit. While resisting oppression, we focus on praxis (action); this is why the latter portion of this essay focuses on advocating for change within the CHC funding process.

Critical psychology also involves recognising our own positions when researching or analysing an issue, e.g., I am a PhD candidate, and I cannot ignore that my level of education absolutely influenced our experience and input within the CHC assessment process. While you are reading this, it is essential to make it known that my account, experience, issues highlighted and potential solutions are informed by my training as a critical psychologist and my political leanings; I am not neutral and do not want to be. I am also not singular; many of the experiences and issues outlined below are not just my own; they extend well beyond just myself or the local CCG, mainly documented in this report from an All Party Parliamentary Group on Parkinson’s: https://chcfunding.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/failing-to-care_appg-ful-lreport-2013.pdf

1) The problematic use of the Decision Support Tool

The most prevalent issue with seeking CHC funding, in addition to many other problems, is that of an unusable and unused tool used for assessments within an MDT. What do I mean? Well, the ‘decision support tool’ (DST) is unfit for purpose and is not utilised to the fullest extent during the review. Here are a few reasons why:

Subjectivity

One of the notions I found the most difficult to comprehend throughout the review process was the idea of utilising a decision support tool, which is inherently rigid (for a purpose; to avoid deeming people eligible for funding, even if eligible). The DST, as mentioned above, involved the scoring of 12 domains. At the same time, indicators of a primary healthcare need that need to be present to be granted CHC funding are nature, intensity, complexity, and unpredictability. How can such a rigid DST be utilised when exploring complex needs? Complex means that which may overlap with each other, and so the rigid need to force Willow’s presentations into a singular domain (e.g., Willow having dementia means that she can often be aggressive, which needs to be considered throughout a variety of domains with which her dementia underpins), implies that such domains are not considered in a complex way, despite the need for such an understanding of complexity.

Such problems are further exacerbated when scoring the domains; service users are further ‘boxed in’ despite some presentations not perfectly ‘fitting’ the description of moderate, high or severe. This is purposeful to ensure people are not awarded CHC funding; they make such scores particularly arbitrary, without any acknowledgement of ‘grey areas’ or middle grounds to argue for the ‘lower’ score. This issue of perpetual underscoring is rampant throughout the review process… This requires an extreme amount of preparatory work for the review meeting to ensure that all complexities and overlaps are covered, usually by a family member or solicitor, and a tremendous amount of confidence to argue a stance which often conflicts with assessors.

The continuous underscoring and problems I have noted with the process are underpinned mainly by outright subjectivity within an argued objective process. Using the DST and companion 200-page document tells service users and their loved ones/legal team that the process of being reviewed for CHC funding is objective, underpinned by seemingly well-thought-through and law-abiding matrices to measure needs and priorities, which, even in 2013 to now, the APPG found clear examples of the guidance not being followed, with no consequences for this.

This is not the case. While subjectivity, as previously shown, is squashed when it comes to loved ones/family experiences of the service users’ presentations, subjectivity is manipulative and employed when it plays the hand of refusing to fund.

Throughout our many experiences with assessors, they often look beyond the domains and their descriptors and rely on an invisible ‘wealth of experience’ and knowledge that we are not privy to, which is utilised more than that of the descriptors, in addition to “further documents” which we asked to see but were never replied to. Assessors say things like: “Oh well, you know it [a scoring descriptor] doesn’t actually mean that-” to which I would reply, “Well, that’s what the DST description explicitly says…” or “[when discussing a certain presentation] In our experience that means someone more like Stephen Hawking…” (yes, an assessor actually said this during one of our MDT reviews).

In addition, I found that CHC assessors disproportionally utilised their power to make decisions that fit their agenda. When questioning such statements like the above, assessors would reply with things like “Well, as a nurse of 20-something years…” or “a dementia need, in my experience, cannot coincide with a psychological need” (which is absolutely incorrect). The issue of a lack of empathy and assessors with specialist knowledge in conditions prevalent seems to have persisted from at least 2013, whereby the APPG noted that more than half of assessments in that year “did not involve a professional with specialist expertise or knowledge in the condition – leading to inaccurate and incorrect decisions on funding”. Positioning themselves as ‘experts’, even without expertise, usually allows them to occupy positions of power, whereby family members or representatives may not feel able to challenge their scoring.

How does such an approach that moves beyond the actual legally binding language included within the DST to an invisible body of knowledge which reinterprets and reinvents scoring descriptions when this works for them, which also reifies power imbalances, promote equity throughout the CHC funding process? Well, it doesn’t. The tool is not used to its fullest. In the words of the APPG: “[CHC funding and assessment] is far from fit-for-purpose”.

Surely, thinking back to this as an objective approach to measuring someone’s eligibility for funding, such a subjective approach does not conform to the overall principles underpinning the design of such a rigid DST tool; this was continually echoed by our solicitor and care home manager: what is on the page, should be how we score service users. The tool is currently unusable and requires profound changes to make it useable and fit for purpose.

While, as mentioned, assessors utilise their ‘expertise’ to squash the opinions of representatives or family members, this is sometimes reversed to fulfil their agenda. Many pairs of assessors we have encountered throughout the process have usually comprised a more ‘senior’ or ‘experienced’ CHC assessor and another who is learning or newer to the process. In one instance, where we (the ‘senior’ assessors and family/representatives) were particularly divided, as the more senior assessor usually leads the MDT, she ‘passed off’ the scoring to her newer and less experienced college to make the decision on scoring Willow on a particular domain. This was not a learning exercise for the newer member but a way to underscore through utilising the inexperience of a less experienced assessor.

A non-adherence to the language in the DST, while ‘passing off’ judgements to less experienced assessors and a lack of acknowledgement of grey areas gives assessors and the NHS the ability to underscore service users throughout the process and thus not receive funding despite the presentation entirely meeting all domains and indicators of a primary health need. Our social worker echoed this and shared that such tactics are utilised to meet budgets. Many local authorities are nearly bankrupt because they are forced to foot the bill for many people in care with a primary health need. This is because NHS assessors, and supposedly those in management, continually refuse funding where people so clearly do meet the criteria for funding.

2) The problem of evidence

A further problem we encountered, which may or may not be prevalent throughout CHC assessments beyond our own, is the issue of evidence. When Willow was first put forward for a CHC assessment due to a change in her long-term healthcare needs, we encountered that before the official DST, the members from the NHS trust who conduct reviews first have a meeting at the care home with a nurse/member of staff to go through notes and histories. This is an important step of the process as the family/support are not privy to the entire contents of the history (unless asked for). This gives reviewers a first impression of the patient, which prevails after many verbal challenges to the scoring throughout the review. All of this information gathering also depends upon the staff available; how well do they know the service user? How well do they know the CHC framework? How well can they communicate the needs of the user? How confident are they? This all shapes the first impressions of the reviewer as the nurse/staff member’s ‘testimony’ is also taken as /evidence/, and so to what quality is that evidence? If poor, I have seen this may devastatingly shape the review, as family/loved ones/legal support testimonies/experience is not viewed as ‘evidence’.

Secondly, as mentioned briefly above, staff members review medical histories, behaviour charts, and care plans to make decisions using the tool/framework during the MDT review. The problem is the quality or quantity of entries within any of the above. In our experience, when Willow was previously in the hospital and during her current nursing home stay, staff had not/do not diligently record her history, presentations or behaviours, which left huge question marks about the validity of our experiences as family members when they were ‘unsubstantiated’ by hospital evidence; for example, Willow had been experiencing dysphagia and would have trouble swallowing food; however, the staff had not been diligent enough or maybe did not have the staff resources, to accurately keep note of/record when such instances had occurred, and so when arguing around the nutrition domain within the MDT, they had not taken this into account because of a ‘lack of evidence’, despite them noting down our differences in scoring throughout the domains. I distinctly remember arguing in said meeting that the lack of records does not mean that Willow hadn’t experienced the issue and that it should not be the service users’ issue that a hospital team, or any team, had not made accurate records, and we found that reviewers often weaponised this discrepancy and ‘lack of evidence’ to underscore the service user on multiple domains; this was rampant throughout our review. This highlights another internal problem of the CHC review process; individualising such an issue without recognising the institutional and structural issues throughout the NHS is challenging to come to terms with and ultimately helps uphold such structural inequalities as very few people win the CHC funding claim.

3) The problem of support

The degree to which we had further resources allowed for additional support from a diverse array of people, mainly family members willing to sacrifice time and those with the expertise, confidence and willingness to challenge decisions, in addition to our expert solicitor. What I worry about, and would have gone to a judicial review for, is the right and access to this level of support for all. What is difficult to think about is that many of these vulnerable people who may be eligible for CHC funding may not be in a position where they are surrounded by family, loved ones or the resources to get that support.

The issue of support is also the problem of attendance. Our social worker was one of the critical pieces of aid we often did not have throughout the MDTs and many appeals. We later learned that MDTs should not go ahead without a social worker, and we [family/representatives] have the right to refuse an MDT when a social worker is not present; I feel that this is another instance whereby invisible rules or expectations of an MDT are not made known to family or representatives to maintain the assessors as the dominant voices in the room…to ultimately refuse funding.

What would have been most helpful would have been the same social worker throughout the entire process, who gets to know the person being reviewed while providing support for those advocating for/with the person being reviewed. It was only at a most recent MDT that we were assigned a senior social worker, and this made one hell of a difference. I can’t help but attribute our win to the presence of and advocacy that the social worker did for ‘Willow’. Not only was he another voice in the room to argue with the opinions of assessors, but he had also previously worked in mental health and was not just a social worker by trade, allowing for his expertise to rival the assessors, whereby they often attempted to use their positions to ‘trump’ our experience. Most importantly, he did not have the same motivations as the assessors – to try to refuse funding through the weaponisation of power, ‘experience or a ‘lack of evidence’, and so, therefore, utilised the DST as it is supposed to be used, as objectively as possible.

From my experience, without that support, I foresee that it would be tough to challenge decisions made by those who do not know the patient/service user well enough within a system that encourages the individual to pay for their own care rather than the NHS funding said person as written into law: “[a person] is…funded solely by the NHS [through CHC], where it has been assessed that someone’s need for care is primarily due to their health needs (a ‘primary health need’)”. However, it is exceptionally murky and subjective as to what a ‘primary health need’ is, and so having additional support who understands the law, whether that be a solicitor who is an expert in this area or family members who may have skills or expertise in law, social care or the critical thinking skills to be able to research and understand the ins and outs of the CHC framework as set out above.

4) The problem of resources

We were lucky enough to be taken on by a solicitor willing to work on a no-win, no-fee basis to support the process of gaining CHC funding. As we know, solicitors usually take on no-win fee cases only if they are likely to win. We felt confident Willow was eligible for said funding and more than met the criteria.

In addition to our solicitor joining us throughout the process and advising us when to take a decision further throughout the appeals process, we also required further resources in terms of our time. Again, luckily, we had my aunt who could work on building our case, liaising with the solicitor and other members of the MPHFT, and attending meetings. However, this is because we are in a somewhat privileged position to either have days off work or work flexibly to participate in these meetings. With such a bank of resources, we could provide the level of advocacy for Willow required to eventually win CHC funding. Without this, we and others may be less likely to be awarded CHC funding.

Recommendations & avenues for change and transformation

Avenues for change and recommendations here will be numbered to relate to the existing problems above. As a critical psychologist, I like to think in terms of dramatic social change, mainly in terms of relevant institutions (e.g., the NHS, policy and law), which will still be outlined here. However, I must recognise that sometimes we have to work with/within a system that cannot be changed quickly or dramatically, so recommendations at the individual level will also be outlined here. As threaded throughout this piece, many of the recommendations set out below were echoed in 2013 by the APPG (pg. 4), which indicates persistent failings throughout NHS England and the CHC process, further exacerbated by austerity and cuts by Conservative governments. For example, in previous years, the NHS wanted CCGs to make £855 million in spending cuts to care by 2020-21, alongside documented policies which set caps on CHC funding, meaning many can only afford the cheapest nursing homes (Continuing Healthcare Alliance). The NHS and/or Government still need to urgently redevelop the system due to subjectivities, breaches of policies & frameworks, and cuts.

1) The problematic use of the Decision Support Tool

One dramatic change that could be made to the CHC assessment process is to make social and nursing care free for all that need it, but that may be daydreaming? Other than the obvious, one change that could be made is redesigning the Decision Support Tool. This is not just based on my experience of the CHC assessment process; problems with the tool have been recognised more broadly via the Nuffield Trust, All Party Parliamentary Groups, books (e.g., Mandelstam, 2020), and in research (e.g., Whitehead, 1994).

As mentioned above, the problem of the tool is very much black and white and deemed objective, yet utilised subjectivity is the main problem; this could be rectified by changing the way people are ‘scored’. One way this could be envisioned is to use a continuum through which people may be positioned, e.g., no needs to priority levels of need, rather than trying to ‘fit’ people into the boxes mentioned above, which we have seen may allow for perpetual underscoring. Although this appears minor in terms of change, actual social change would be to make nursing and social care free for all, and we shouldn’t settle for neoliberalism.

If such a rigid tool has to be used to assess, it should be used to the letter across all local CCGs. No interpretation. The words on the page of the DST are those that a person is assessed to, not some unfounded and abstract knowledge or experience that is not shared amongst all in the DST. One stark example of this is that for CHC funding, the person should have a primary healthcare need. Yet, there is no legal definition for this, leaving the assessors to make decisions based on their own subjectivities. If further experience is needed or used to understand terms within the DST, e.g., “often”, this should be quantified and shared amongst all in the DST to hold such assessors accountable. This would also ensure further standardisation across NHS CCGs.

To improve the assessment process and tool further, as below, further columns within the DST could be included to allow for accountability of scores attributed to domains. This could also be accompanied by reasoning as to how and why they reached such a score; currently, the assessment report is written after the MDT by one assessor; however, if this was done collaboratively, this would allow for further transparency of using the DST, the assessment process in general and a flattening of power hierarchies across those who attended (and scored) within the MDT. Again, if this is not possible, feel empowered to make notes throughout each MDT to hold others and their scoring accountable.

Another option for change would be to allow for a more thorough familial/representative contribution to the CHC assessment process. When we talk about challenging some of the assessors’ scoring during the MDT, assessors say things like “we will note that down” when families/representatives have a different score in mind for a specific domain. But did they note it down? How? Where? Would that have any impact going forward if it was written anywhere at all? What would be beneficial would be to add a relative/representative contribution/experience column to the DST. This would give confidence to relatives and representatives or the person being assessed that their experience means something and is important to the medical/health professionals conducting the MDT. Currently, there is a ‘relatives contribution form’ which can be filled out during the assessment process, but from our experience, this is not always sent out, asked for or utilised. However, looking individually, I recommend printing out your own DST to note your/your relative’s positions on each domain throughout the MDT and making notes throughout (e.g., of any failings, points to feedback or elements missed).

2) The problem of evidence

Throughout my time with Willow in various medical environments (e.g., hospitals or care homes) and various MDTs, it has become prevalent that medical professionals, those in positions of power, continually disregard my or other relatives’ thinking or experiences of Willow’s conditions or presentations. I do not disregard that such professionals (e.g., assessors) have a wealth of experience and professional training to understand those under assessment. However, the problem occurs when attempting to give verbal evidence within an MDT from a position of knowing your relative to the utmost degree, which leads to a struggle for power during MDT meetings to assess CHC eligibility. One proposed assessment process change would be establishing an equal power hierarchy. There are multiple ways this can be accomplished; through transparency (a cornerstone of authentic leadership; see Kempster, Iszatt-White & Brown, 2019), participatory collaboration, expectation and goal setting, and shared facilitation (to name a few), in addition to thorough training on meeting facilitation, empathy, and standardised education on CHC guidance and case law.

As mentioned above, assessors immediately occupy a position of power, which reproduces the division between ‘us’ and ‘them’. This is not only harmful when negotiating each of the domains but also has the consequence of dehumanising a person being assessed. I think this further leads to the cognitive dissonance of assessors in recognising the person on paper as a person, not just a series of complexities, conditions, and behaviours. If this is not possible, to think individually here would be to try to continually occupy positions of power, mainly through occupying the position of expert, of your own complexities, histories and experiences. Ensuring your voice is heard, share your own evidence, take notes, and, if required, make complaints about the process and appeal.

The above is further confounded as, as I have mentioned previously, there is a rampant issue of evidence, and when providing verbal evidence to make up for presentations, occurrences or conditions which have not adequately been recorded, these are taken as unfounded, untrue or attributed to a lack of understanding on our part, without thinking of criticising the institutions of care whereby workers are working under an ever-demanding system whereby perfect record keeping cannot exist. This then disproportionately disadvantages those who need care. To remedy this, as above, you consider making notes yourself or going beyond to create a thorough medical history to substitute for lack of or contradictory evidence. Or, more dramatically, the NHS and assessors could be trained or further guidance designed to allow for the importance and validation of verbal admissions of evidence; this would allow for an acknowledgement of how the person being assessed is not responsible for their lack of records and that these can be further substantiated despite NHS/hospital/care home failings.

3) The problem of support

As mentioned, advocating for another person or yourself throughout a CHC assessment is daunting. One of the more dramatic institutional changes that could be made to further support those throughout the process would be to include a brief on who should attend each MDT meeting and hold assessors accountable for ensuring that the correct people are in attendance. If not, then meetings should be rearranged. People should know what rights they have to refuse or rearrange meetings to ensure that a variety of diverse voices refuse the furthering of particular institutional agendas. If nothing else, ensure you attend all review and appeal meetings; take notes throughout (e.g., what was said and who said it).

In addition to ensuring that all those who should be in attendance are in attendance at MDT meetings, the site of reform is then cast upon the professionals who know the person being assessed best. In the guidance for the assessment, it mentions that the MDT should be comprised of at least two health or care professionals who are already involved in the patient’s care; for us, the assessors themselves were not already involved, and so they conducted meetings with Willow’s nurses and care home manager. However, the two professionals were inconsistent across MDT meetings, and we had no say in who was involved. Some nurses/professionals knew/know Willow better than others, and so to have professionals involved who can share more evidence from a professional standpoint while knowing the person sufficiently would likely lead to a more favourable chance of meeting eligibility, especially if facing similar issues to us of a lack of recorded historical evidence of each domain.

Further, I advocate for anyone to seek free legal advice, and there are multiple ways to do this: free legal advice, such as BeaconCHC, advice from charities, such as the Alzheimers Society, or independent websites, such as Care to be Different. Try to keep communication open between you and your allocated social worker (if applicable); the more they know the person being assessed and their history, the more they can advocate during the assessment. If possible, have multiple people attend the MDT; this creates a more balanced power hierarchy if not encouraged by the assessors themselves; more voices means further space taken up by those with a more nuanced and extensive perspective of the person being assessed.

4) The problem of resources

Lastly, the problem of resources is the most dependent upon your/the person being assessed’s situation. One of the most prevalent problems is time, especially if you want to advocate for your relative/others sufficiently; this requires a lot of time to plan and set yourself up to challenge assessors and the system rather than just showing up to the MDT without preparation. Most of us are juggling family, full-time jobs, studying, caring responsibilities and more, which is why I suggest finding others to support during the process. If you and others have the time, use this wisely to familiarise yourself with the guidance, processes, National Framework (consider your own weightings) and tools used throughout the assessment, and even case law if you can and have the confidence and time to do so; the more information you have, the more you can advocate, and be persistent when advocating; even when frustrated, do something with your frustration, document everything and make complaints where required.

In a perfect world, each person being assessed would be allocated a solicitor, who could help you understand the ins and outs of CHC assessments and appeals; however, living in a resource-light society, where resources are often shared so thinly, means that it is up to individuals who have enough capital to afford their own resources.

Further to familiarising yourself with all aspects of the CHC assessment process would be to know yourself or your relative. Of course, retrospectively, if we could go back to when Willow’s conditions became more complex, we would have kept diligent, dated notes. However, this is far removed from reality. I suggest reviewing the DST’s domains, writing key points to share, and your weightings within the DST or appeals meetings. To do this thoroughly, gather evidence (request medical records and any further evidence from professionals, e.g., changes to care plans to showcase a healthcare need), and ensure this is filed effectively; this will be beneficial if you are persistent enough to go through numerous reviews and appeals.

If advocating for others in care, I would recommend asking to review their care notes/plan/behaviour record (etc.) to ensure that the evidence is there, is consistent with your experience of your relative and to ensure that you know the status of your relative’s conditions (etc.). This means that, within the meeting, you can assert yourself as an expert, assuring that your voice is heard and scores are taken seriously.

Conclusion

In summary, CHC assessments are formulated in such a way as to ensure that most do not prove eligible for funding. We cannot deny that this is due to the hegemonic pressures the NHS currently faces due to numerous cuts. I have outlined ways to empower yourself throughout the process to increase your chances of being deemed eligible for CHC funding or to advocate for others. I encourage all reading this to fight, question and attempt to transform the CHC assessment process, assert the position of expert and challenge others.

References

- Kempster, S., Iszatt-White, M., & Brown, M. (2019). Authenticity in leadership: Reframing relational transparency through the lens of emotional labour. Leadership, 15(3), 319-338.

- Mandelstam, M. (2020). NHS Continuing Healthcare: An AZ of Law, Practice, Funding Decisions and Challenges. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Teo, T. (2021, March 25). History and Systems of Critical Psychology. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology.Retrieved 11 Jul. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-663.

- Whitehead, M. (1994). Equity issues in the NHS: Who cares about equity in the NHS?. BMJ, 308(6939), 1284-1287.

Call for comments

If you have any comments, questions or experiences you would like to share, please do leave them below or email me.

Leave a comment